Tracking the Wildlife Protection Act through 50 years

India has paid a heavy price for its economic growth in terms of its environment and conservation measures. Fifty years since the enactment of the Wildlife (Protection) Act (WLPA) 1972, one of the most comprehensive and stringent legislations in the world, there is a felt need to look back and question where we have gone wrong. At the same time, a glimpse into the future will allow us to see where we are heading, says a new book.

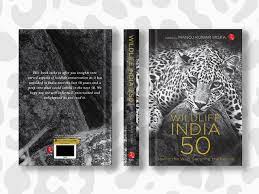

Marking 50 years of the … legislation, the book, Wildlife India @50: Saving the Wild, Securing the Future, a compendium of 30 writers, put together by former forest office Manoj Kumar Misra, brings to life India’s journey from its low point in 1969, when a wake-up call was sounded at the Tenth General Assembly of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), held in New Delhi. The legacy of hunting and habitat loss had taken a heavy toll on India’s wildlife. The tiger numbers were dwindling, the Asiatic cheetah was extinct and several other species were on the brink.

The ensuing WLPA 1972 was a national wildlife legislation that set the ground for firm action to protect wild animals and their natural habitat. Apart from launch of Project Tiger in 1973, new wildlife protected areas (PAs) in the form of national parks and sanctuaries were created all over the country. The Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun, was established as a premier institution in 1982.

In two decades since the inception of the Act wildlife and their habitat showed a marked growth. Tiger numbers rose and several animal species, such as barasingha deer in Kanha National Park, were pulled up from near decimation.

It was in 1991 that India opened up its economy to adopt the wester market-driven model for faster economic growth. From 2000 onwards, the book states, a sudden brake was put on the missionary zeal of the 1970s and 1980s to promote wildlife conservation in the country.

Mapping the five decades of the journey, the book is a narrative through the eyes of 30 diverse set of writers, who have experienced first hand the dynamic diversity of the country’s wildlife. They include forest officers, researchers, environmentalists, activists and journalists. Their stories are not fictional but “lived” tales.

The book has been divided into two parts. The first features authors reflecting directly on matters that relate to the WLPA. The second section deals with it indirectly through personal tales about people, projects and institutions.

The book opens with Suresh Chandra Sharma, a former forest officer of the Uttar Pradesh cadre, who later served as the additional director general of forest (Wildlife) in the Ministry of Environment and Forests. He describes his incredible journey as an insider with the government for 15 years, when he witnessed the process and politics of law making.

H S Panwar, the founder-director of Kanha Tiger Reserve, highlights the necessity of inviolate wild spaces, recalling his decade-long Kanha days marked by a remarkable recovery of the threatened barasingha.

Dr Asad R Rahmani, former director of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), has written about his interactions with his guru, the famed ornithologist, Dr Salim Ali.

Veteran journalist Usha Rai has given a candid version of her experience right from the time she joined the Indian Express as a trainee journalist. She aptly describes environment writers, “Most journalists are not subject specialists. They learn on the job by contacting those with knowledge and information and, like the chital and the barasingha, keep their antennas up.” Despite her 50 years in journalism and environment reporting, Usha harbours a sense of disillusionment. While there are a still a few highs now and then, she says our forests and wildlife continue to shrink and there is a “crazy rush for development, even if it is not sustainable!”

In his chapter, Manoj Kumar Misra describes the 1990s in India as being, in many ways, a watershed decade. It began in 1991 with two “almost paradoxical developments”. India opened up its economy, bidding goodbye to the “mixed” pattern of economic activity, where public sector and private sector led an uneasy coexistence. The western-style free market system allowed private sector to receive preference over public sector for a faster rate of economic growth.

At the same time, Misra writes, a conservation-oriented WLPA underwent a significant revision in 1991 to skew it firmly towards protection, with the deletion of a few provisions in Chapters III and IV that permitted limited hunting and use of wildlife. A large number of protected areas (PAs), in the form of national parks and sanctuaries, were created. Enforcement action against what was till then “legitimate wildlife use and practices” became the order of the day. Traditional hunting and taxidermy became illegal as did trade of common wildlife items like ivory, skins, furs, horns and antlers.

Soon enough, the two developments clashed and colluded in the form of underground wildlife trade. Professional hunting tribes and willing conduits became easy tools in the hand of illegal mafias. “After all, in an open economy, making money legally or illegally comes easy,” notes Misra

About the book:

Wildlife India @50: Saving the Wild, Securing the Future; Edited by Manoj Kumar Misra; Publisher: Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd; Pages: 517; Price: Rs 995

.png)